Part I

29 March, 2006

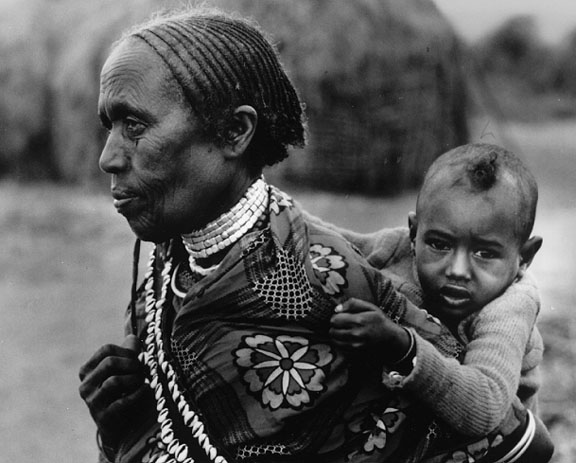

As the drought lingers in Ethiopia, the cattle die, and the people work to find new ways to live -- ways that are not part of their history and traditions. But if they are to have a future, some things must change. Oxfam's Liz Lucas recently revisited part of the stricken region -- here's what she saw.

The Animals are the First Sign

I'm going back to Borena. I haven't been down south in a month and with that comes a certain anxiety: Has it gotten much worse? My work at Oxfam has focused on the drought. Lately I've been reading reports and following up on the situation as much as possible, but I've learned that the best way to really understand it is to speak with those affected.

The road is familiar to me now and as we head towards Yabello it is not only the scenic mountains, the acacia trees, and the change in costume that let me know we have almost arrived, nor the carts heading south. The most obvious sign is the animals. As the cows become skinnier and weaker, I know we are getting further into Borena, the zone in southern Ethiopia that is among the areas most hard-hit by drought in the Horn of Africa.

I am returning as part of a communications team, along with Greg (media officer), Steven (a cameraman), and Retta (an Oxfam livelihoods officer). Our mission is to document the drought and try to make people in the US care about a lack of water thousands of miles away. It can be the hardest part of our jobs.

Amid recurrent drought and conflict in Africa, the death of livestock doesn't always sound particularly impressive to the average reader. However, what these animals symbolize for the nomadic herders (called pastoralists) that populate the area is a future and self-sufficiency. With their death comes also the weakening of hope.

In the Land Cruiser I try to sleep, knowing that the next few days will be exhausting. I’m awakened mid-doze by a slight mist on my arm. It’s beginning to rain in Borena and the ground has turned a deep red. The tires are spewing mud instead of creating the dust cloud that I was expecting. The landscape changes color, and outside children run along the side of the road with jerry cans full of water. There are splotches of color as umbrellas often used to shield people from the sun are now opened to keep them dry.

In the car the mood is altered -- we are here to tell the story of a drought and there is rain. We’re all excited about the prospect and what it means for local communities. But how do we film a drought while it is raining? I wonder if that is the story to tell right now.

Oddly enough, it is this shower that may now kill the livestock. After months of insufficient food and water, the animals are so weak that the cold front that brings the rain could kill them.

And the rain in all likelihood will not be enough. The National Meteorological Service Agency has reported that the Belg rains (normally March to May) would most likely be late and insufficient to meet people's needs. Even when new vegetation sprouts, there must be enough rain to wash the acidity from the grass or else the livestock will become sick. Oxfam is providing emergency veterinary supplies to livestock for this very purpose. It will take them a long time to recover, even after the grass starts to grow.

Living is precarious in this part of the country with the constant challenge of water and pasture. In years past we built projects to ease the burden on pastoralists, particularly women. Those Oxfam projects continue to have an enormous impact on lives and livelihoods. In this current drought they stand as examples of projects that not only help during humanitarian emergencies but also build long-term solutions.

During my last visit, a village elder told me that Oxfam water projects had kept his community alive so far, despite the prolonged drought. The weather forecasts have made us nervous, but it is of some comfort that these water stations continue to function even in the most challenging of circumstances.

Tomorrow we are going to begin filming a story about the drought, but there is another story to be told. The rains may come and they may make people shake their heads and think twice about the situation here and its importance. Yet to me, the rain is the most poignant part—the quick switch between life and death, normalcy and crisis.

Today the situation is improving because of the rain, but I wonder if, in a week, a month, even a year, the situation will turn around again and the people will be stuck in the same cycle. This time, however, after another "false alarm," they will be even less likely to get emergency aid. Development and investment in long-term changes here are needed to help people help themselves and cope with nature’s constant challenges. No one deserves to live in a constant state of flux, receiving help only when faced with devastation that is too late to remedy.

www.oxfamamerica.org

No comments:

Post a Comment