Bread and Bullets: a Somali tells of how he picked up a gun to guard for survival

The Associated Press

December 9, 2007

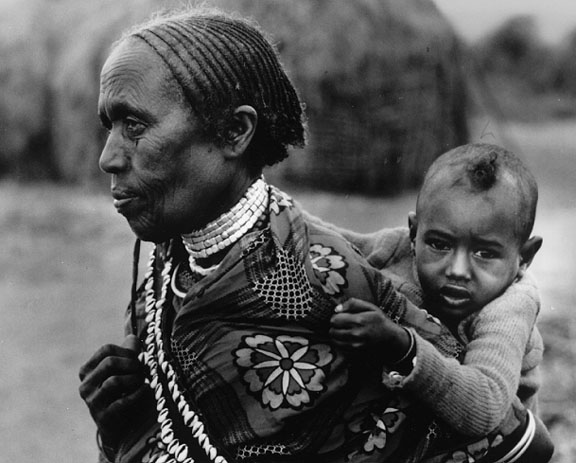

MERKA, Somalia: Like all fathers, Mahmoud Farah wants a better life for his son — but unlike most, the only way he can get it is by working as a gun for hire in the chaos of Somalia's civil war.

International attention has been focused on the Horn of Africa conflict by the presence of Islamic insurgents linked to al-Qaida and the involvement of Ethiopia and Eritrea, two regional powers fighting a proxy war in Somalia. But until diplomats can come up with a better future for men like Farah, a 40-year-old former waiter, stability will have few attractions for the tens of thousands of gunmen that flood the country and whose only living comes from policing — or fomenting — the violence.

After nearly two decades of civil war and anarchy, the best job the former militia member can hope for is guarding desperately needed food shipments with his battered rifle.

"I don't carry the gun for political reasons, I carry it for my bread," Farah said recently, speaking with The Associated Press in the seaside town of Merka as hungry Somalis lined up for a share of the 3,600 tons of World Food Program rations that he was guarding. "If my bread is attacked I will fight."

He first picked up a gun in 1991, when Somalia was imploding after the fall of dictator Mohamed Siad Barre. The restaurant owners he worked for had fled the city as rival warlords battled each other in the streets of the capital. Farah joined one of their factions.

"The gun gave me power, even though the war was the worst time of my life," he said, the sun glinting off the lines of rifle cartridges slung across his skinny chest. "Many of my friends were killed. Every death broke my heart, but when my brother was killed by a stray bullet, that broke me."

After his brother's death, his uncle convinced him that devastating the city with the militias and looting food for starving children was dishonorable. The uncle employed him as a bodyguard — one of Somalia's few growth industries — until he found work with the United Nations last year. In the pervading insecurity, bodyguards like Farah are an indispensable part of aid operations and business in Somalia.

The arid Horn of Africa nation is effectively a failed state, whose 14th successive transitional government is fighting for control amid an Islamist insurgency and continuing clan-based violence.

An Islamist group, some of whose leaders are on a U.S. government list of wanted terrorists, briefly took power in the capital and parts of the south last year before Ethiopian troops supporting the transitional government forced them out. Now the United Nations says Eritrea, Ethiopia's archenemy, is helping the insurgents even as Ethiopian troops flood the capital in support of the corrupt and shaky government.

According to a recent human rights report, fighting in the capital of Mogadishu has killed 6,000 people this year, and forced 600,000 people to flee their homes.

These people now desperately need food aid, said Peter Smerdon, the regional spokesman for the United Nations World Food Program, but the insecurity means the agency struggles to get food to all the civilians who need it. "Roadblocks and piracy are making it very difficult to reach people in need," Smerdon said.

So aid agencies employ people like Farah, who lived and worked in Mogadishu until the Ethiopian army entered the city at the behest of the government. Having lived through the chaos of the militias and the Islamic victory, the lean, grizzled father of four was among the first wave of refugees to leave the city when the Ethiopians came in. The government's decision to invite the foreign soldiers to do their fighting left a bitter taste in his mouth.

"Our enemy is Ethiopia, and the enmity is very old," Farah said, spitting on the ground to show his disgust. "Our government is stabbing its own people in the back."

What saddens him even more is the way Somalis have been divided.

"Some Somalis are clapping for the Ethiopians while others are crying, and it's just because of our hatred toward each other," he said, the deep lines in his lean face furrowing even further. "If they would just leave us alone, I am sure Somalis would solve their problems the way they did in the old days. Under a tree over a cup of tea."

Even the persistent droughts and famine that gripped the country did not extinguish traditional sense of Somali community, he said. When he was 7 years old and his father's entire herd was wiped out in the 1974 drought of 1974, he recalled, his neighbors insisted he be evacuated on a plane before them.

"My feet never touched the ground. People carried me on and off the plane because back then, people really cared for each other," he said. "Today there is so much clan hatred nobody cares for anyone."

Farah can earn up to US$100 (€68) a month as a hired gunman. The money has enabled him to marry and provide for four children. He dreams that his oldest son, 8-year-old Ibrahim, will one day go to school. In that modest dream, Farah finds more hope for the future than in the thousands of pages of documents or years of negotiations that have deadlocked Somali politics for so long.

"I feed my family with the gun, but I would never let my son carry one," he said, cracking a rare smile with his stained teeth. "The gun brings too many problems."

International Herald Tribune

No comments:

Post a Comment